« Which family? » Julia asked. « Because it wasn’t the best for the person you brought into the world and then stole from. »

My mother didn’t have a ready-made answer. She said nothing. Sometimes silence is the first opportunity for the truth to emerge.

My father held on for six minutes before erupting into such a violent rage that the building’s air conditioning wondered if it should even turn on. Julia didn’t react. She let the anger run its course until it subsided.

Mr. Harrison, did you list Beverly as a dependent on your tax return between 2019 and 2023?

“We gave her moral support,” he said.

« It’s not deductible, » Julia said. « Yes or no. »

“Yes,” he answered curtly.

Did she live with you?

« Nee. »

Did she pay her own bills?

« Yes. »

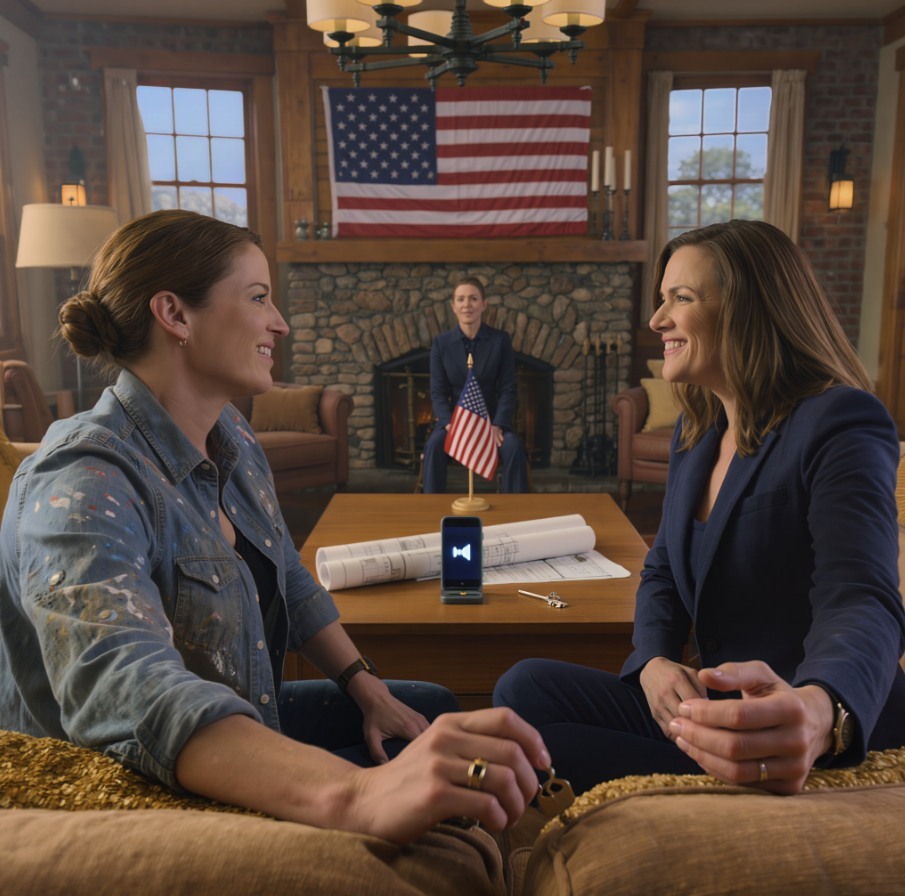

“Thank you,” said Julia, and she walked away like a surgeon who has just tied a perfect knot.

On a rainy Tuesday, a note suddenly appeared on my door: Notice of Seizure – Labor and Materials. A contractor I’d never met—a guy Randy had had problems with before—had wrongfully seized my property, likely on my brother’s advice, trying to flood my house with paperwork like a cheap bartender watering down his whiskey.

I took the newspaper to Julia. She smiled humorlessly. « Ah, the well-known trick of the privileged on the gravel driveway. »

Can we make it go away?

“With prejudices.”

On Friday, the privilege was lifted, the contractor’s lawyer apologized in a letter that sounded like it was from a man Julia had met once and didn’t want to see again, and we obtained a court order that makes future false statements punishable by a fine that would frighten even Randy.

I felt as if the invisible walls around my house were extending outward. The earth isn’t just dust. It’s the stories hidden within.

The IRS called. Agent Morales had a deep, controlled voice, like an old-fashioned filing cabinet. « Ms. Harrison, thank you for your cooperation. You may be called to testify if the case goes to trial. In that case, your lawyer can accompany you. »

“Is there a world where this doesn’t happen?” I asked.

« Not this one, » he said, pausing. « They filed amended statements yesterday. It’s… advisable. Besides, it’s an official confession. »

After the phone call, I went to the greenhouse I’d built with my grandmother’s small savings and checked the heating. The glass panes rattled in the rain. Despite everything, the delicate plants were growing well. I picked some basil to fill the room with its fragrance and create a more pleasant atmosphere.

On the day the agreement was signed, Winter finally made a decision. The agreement was simple: repayment of the $200,000 with interest at the legally established rate, deposited in an escrow account overseen by a court-appointed trustee; payment of attorney’s fees; a confidentiality clause combined with a lump sum liquidation clause, providing for the double payment of my mortgage in the event of breach of contract; and a foreclosure clause that would convert any default into a judgment I could file against all the properties Winter seized, including the future estates of anyone unwise enough to leave them money.

« We’ll keep a close eye on them, » Julia said. « And if they even bat an eye, we’ll punish them. »

« They sold the house, » Juan added softly. « The sale closed last week. They’re renting now. »

I agreed. I didn’t cheer. I wasn’t happy. I went home and made soup, because sometimes justice needs fertile ground to take root.

That evening, I registered my deed to a revocable trust in my name. Julia had me fill out a declaration of principal residence. We added a transfer-on-death clause to ensure that no one could ever again claim that what was mine belonged to someone else.

« Go to sleep now, » Julia said. « The law protects you. You can always protect yourself. »

What to do with the peace? We can squander it by searching for a new fire. Or we can learn to live with it.

I painted the dining room a moist earth tone. One Sunday, I hosted a potluck for the neighbors who’d waved to me from their porches while I was replacing the siding, in an August that seemed to drag on forever. We set up folding tables, and I wrote the place cards with a hand that no longer shook. Mr. Patel, from 4B, brought lentils that tasted like the food of a man who had resolved to forgive everyone who had wronged him. Elena, from across the alley, brought a wedding cake and confessed she’d made it as practice, dreaming of one day opening a bakery specializing in celebratory cakes.

When the last plate had landed in the colander, I picked up my grandmother’s notebooks. I read one aloud, the one about bridges and scouting. A silence fell in the room, a silence in which you could sense everyone resolving to be kinder. We passed the notebook around, as if it could bless us if we just held it tight.

The following week, a woman from the community center asked if I could teach a Saturday workshop titled « DIY: The Five Basic Tools. » I agreed, before my old hesitation had a chance to question why I thought I could handle it. Ten people showed up. We learned how to turn off the water tap without crying, how to patch a hole without apologizing, how to decipher a contractor’s quote as if it were a lie—because sometimes it is. The following Saturday, twenty people showed up. The third time, the hall was packed.

I called the course « Hands and Hammers. » Julia registered the club before I could even bring myself to wait. Juan created a website that looked so sleek and professional. Sloane developed a budget that didn’t pretend money could work miracles; she made it possible with math.

“Do you want to teach tax law?” someone asked him.

« I’ll teach you to be careful, » she said, smiling. « And how to immortalize joy. »

One day, I ran into Grace in the almond butter aisle at the supermarket. It looked like a comedy scene from a low-budget movie. She looked happy, genuinely happy, without makeup. We stopped by the bulk bins and told each other the truth, without having to pretend to be magnanimous.

« I kept the ring, » she said. « I bought it on credit. I sold it to pay off my loan. »

« I’m giving a lecture on the difference between fraudulent and honest money, » I said. « You could be a speaker that day for free. »

She arrived. She explained to twenty women and five men how to distinguish a person from a plan. When she left, two students hugged her as if she had given them a year of their lives back.

Spring arrived. The courtyards gave way to crocuses. Payments poured into the escrow account like rain in a well-tended garden: regular, sufficient, and controlled. My father found a job at a hardware store because men like him can no longer tolerate the silence they’ve imposed. My mother created a Facebook group called « Family First » and posted quotes about loyalty that made my teeth gnash. I unsubscribed without hesitation, as if it were a victory.

Randy opened and closed three businesses in six months. The third, a « real estate consulting firm, » closed the day he wanted to use a photo of my house on his website. I then asked Julia to send a sharp letter. He removed the photo. He stopped texting me from new numbers. When he ran into Juan in town and wanted to talk to him, Juan called me first and said, « Your brother was trying to borrow my ear. »

“Did you lend them to me?” I asked.

« I have a fair use policy, » he said. « Abuse is not acceptable. »

On the anniversary of the phone call that set it all in motion, I stood on the front porch, coffee in hand, enjoying the peaceful morning without a care in the world. The house breathed, like a living being. A faint light filtered through the conservatory window. In the bay window, my reflection remained undisturbed. I looked like a woman whose name lived up to her deeds.

I dug out my grandfather’s old spirit level, which I’d found in the wall that first week, a persistent glass bubble like a beacon of hope, trapped in a tube. I placed it on the dining table and watched the bubble center itself. The wood had stabilized. And so had I.

“Accounting balances,” Julia texted me when I sent her a picture.

“Not just money,” I replied.

“No money at all,” she replied.

Six months later, the district attorney called me. A young assistant district attorney named Watkins asked me if I’d be willing to give a victim impact statement if the state accepted a guilty plea in the inheritance case.

« I don’t want to see them orange, » I said. « I don’t want to see them at all. I want to plant tomatoes. »

« You can do both, » he said softly. « The justice system is capable of handling multiple tasks simultaneously. »

I wrote this statement at my dining room table, which I had sanded and oiled with my own hands. It was certainly about money, but also about that night I sat in my car and cried, convinced my grandmother had deemed me unworthy to inherit her faith. I wrote about the sound a house makes when it’s told it might have to leave, because you can’t wage war and repair a roof at the same time. I wrote about the relief of a judge who had issued a « ten » order, and who actually meant it.

During the preliminary hearing, the courtroom was so small you could hear every swallow. My parents stood there with their lawyer and seemed smaller than I remembered. The judge asked me if I wanted to speak. I replied, « No, but I’m going to anyway. »

I kept it short. « You taught me to earn love. That’s not true. I earned my home. You don’t live there. »

Later, in the hallway, Julia shook my hand again and then let go. Watkins had tears in his eyes, but he claimed it had nothing to do with the case. The agreement was mainly about damages and penalties, since the IRS had already paid its share. That was enough. A full meal was more than enough.

Hands & Hammers grew as high-quality projects often do: slowly and effortlessly. We rented the back of a solidly constructed warehouse with weathered paint and converted it into workspaces using recycled doors. Thursday evenings were time for the « tool library »; Saturday mornings were workshops with « advice for entrepreneurs »; and Sundays were writing circles where women wrote emails to their landlords, bosses, ex-partners, and the cities that had underestimated their courage. Above the door hung my grandmother’s words: « Money is a tool, not a leash. »

Once a month, Sloane taught the « Coupons for the Soul » workshop, a budgeting workshop for people who considered budgeting a prison. She matched their receipts to their life stories until the numbers reflected their true nature: choices within a lifetime.

Julia came by once to teach us « How Not to Be Exploited. » She brought donuts, because sometimes the law can be fun. She wrote four sentences on the board and had us repeat them until we could recite them without running out of breath: « Write this down. » « What law are you talking about? » « I need 24 hours. » « No. »

Juan taught us how to « preserve the traces of lies. » He showed us how to save text messages, summarize phone conversations, and email the facts to each other so that time wouldn’t alter them. He always said: « Memory is generous. Evidence is accurate. Be kind to yourself: be precise. »

The first time a student sent me a photo of her signed deed, I burst into tears in the supply closet where we keep the good screws and the level that still hits the center every time.

At the end of the summer, I found a note tucked between the bars of my fence. Not from my parents. From Aunt Martha—the same one who’d sent a message like « How could you do that? » in the group chat before leaving like a kindhearted soul who’d set a room on fire. The note was shaky, but sincere.

— I was wrong, Bev. I believed them because it made my life easier. I’m sorry. If you ever need me to care for plants, dogs, or a broken heart, I’m here for you.

I stood there, note in hand, letting the pent-up anger I’d been suppressing evaporate like dew. I replied and slipped my letter into her mailbox. I said, « Come with your hands. We have a sanding table. » We sanded. We didn’t talk about the group chat. We talked about the wood grain and, through the effort, rediscovered our true selves.

On a rainy Wednesday, Julia called. « The last payment on the escrow account has been made, » she said. « The account is a circle. »

“And now?” I asked.

« Now plant something ridiculous, something fragile, and something that will probably die in your climate, » she said. « You need to practice losing things other than houses. »

I bought a fig tree. I named it Calendar, because it taught me to treat time with respect. In October, it gave me two figs that tasted like perseverance. I ate one barefoot in my kitchen. I gave the other to Mr. Patel, who had told me in April that if I learned to grow figs in our region, God would give me a promotion.

Sometimes, late at night, I still hear my father’s voice echoing through the static. I don’t pretend the ghosts don’t exist. I just don’t open the door. I keep a copy of the bylaws in the freezer, because paper and soup are the only two things I’ll never be without. I keep my grandmother’s diary next to my bed and have her describe what happens to bridges when they’re built by people with a scouting eye.

When the women in my class ask me if justice is worth getting bogged down in paperwork, I tell them the truth: paperwork is like a rope thrown over a wall so you can climb over it. It takes time. Your arms ache. You get a splinter you can’t seem to remove. Eventually, you find it. And then you throw the rope back down for the person behind you.

One evening, Cass came into my kitchen and touched the doorframe where Randy had scratched the door. « I can’t stand it anymore, » she said.

« It’s not there, » I said. « I sanded it until the wood was back to its original shape. »

See more on the next page

Advertisement